Family Meetings for Conflict Resolution

by Aletha Solter, Ph.D.

Originally published in Mothering Magazine, Issue 118 May/June 2003

"If you don't stop that, I'm going to put it on the agenda!"

When I overheard my ten-year-old daughter yell this to her teenage brother one day, I realized how important our weekly family meetings had become. I highly recommend family meetings for parents who want to become less authoritarian with their children without becoming too permissive. Weekly meetings provide a forum in which family members can resolve conflicts in a truly democratic way. Anyone can bring up a problem, and everyone participates in finding solutions and making rules. Family meetings can work well with children as young as four years.

Getting started

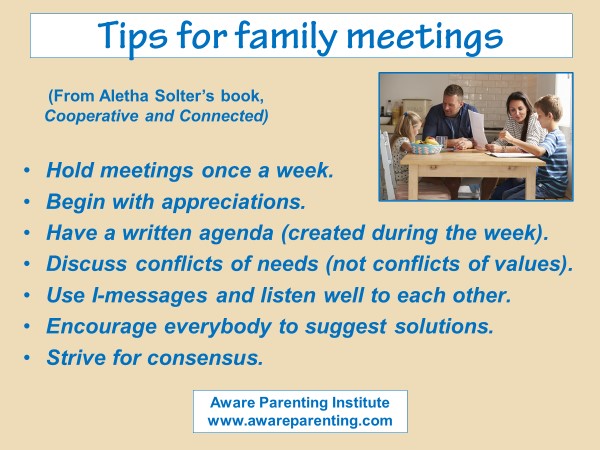

A good way to start having family meetings is to propose a regular, weekly meeting time. Our family held its meeting on a specific evening each week during dinner. If we could not all be together on that day, we tried to set another time that week for the meeting. You can use your first meeting to discuss the structure of future meetings, as well as the decision-making process.

It is important to have a written agenda. In our family, we taped a blank sheet of paper to our refrigerator door, where family members wrote down the items they wanted to discuss, along with their names. This became the official agenda for the next meeting. (Children too young to write can dictate their agenda items, or draw a simple picture.) Meetings work best if no one adds any items to the agenda once the meeting has started. In order for meetings to run smoothly, there needs to be a chairperson and a secretary. These responsibilities should change each week so that each member of the family has a chance to participate in the leadership; as soon as children are old enough to do these jobs, they should have their turn. The chairperson's job is to see that each agenda item is addressed in order, to ensure that no one interrupts the person speaking, and to keep the discussion on the topic at hand. The secretary writes down the decisions reached.

Giving appreciations is a wonderful way to begin meetings. The chairperson can begin by asking if anyone has an appreciation for another family member regarding something specific the person has done during the week. In our family, we sometimes had many appreciations, at other times very few. For example, I once appreciated my children for helping out by doing extra chores when I was sick. On several occasions they thanked my husband and me for helping them with homework.

After appreciations, it is useful to have an announcement time when family members let each other know, for example, if they are planning to be absent for a meal or out in the evening during the following week. This becomes increasingly important as children grow older and participate in numerous activities.

After announcements, the chairperson can then follow the written agenda, addressing each item in order. Some families may wish to decide on a time limit for the meeting, while others may think it is more important to finish discussing every item on the agenda. In any case, meetings should have a definite end; it's fun to end with a special dessert or a short game, if time permits.

Agenda items: the specific content of meetings

Here are some examples of conflicts that we discussed in our family: use of the bathroom, chores, reading at the table, disappearance of pencils from the kitchen drawer, leaving lights on, going into people's rooms without knocking, messes in the living room, and use of the living-room couch. We solved all of these problems during family meetings, to everyone's satisfaction.

Sometimes parents who consult with me report that their children are at first resistant to the idea of family meetings, thinking that this is merely a new trick to get the children to do what the parents want. When this occurs, I advise the parents to restrict the agenda items of the first few meetings to pleasant topics that are not emotionally charged, such as planning a family trip or discussing how to celebrate an upcoming birthday. Even after meetings are a well-accepted routine, I recommend using them not only for conflicts, but also for neutral topics.

It is also important to encourage the children to use the meeting format for problems they have with their parents, or to address situations in which they feel that their needs are not being met. My son once brought up a problem he had with us playing music in the living room while he was trying to do his homework, so my husband and I agreed not to play music while he was studying. (His room was right next to the living room, and the walls are thin.) A year later, when he acquired a drum set, he was quite willing to work out a solution at a family meeting when we told him that the noise bothered us. The solution we reached was that he would play his drums only when he was alone at home.

In most families, discussions of chores usually take up a good deal of meeting time, at least at the beginning. To get started with this, it is helpful to use a meeting to make a list of all the jobs that need to be done daily, weekly, and monthly. Be sure to include in this list all the jobs the adults do that might otherwise be taken for granted, such as earning money, paying the bills, and shopping for groceries. One way to divide up the chores is to ask for volunteers to take responsibility for each one. After you reach agreement on this, someone can write up an individual job list for each family member.

Another way to assign chores is to rotate them systematically among family members each week or month, or distribute them randomly at each meeting. There are many creative solutions, and whatever system your family agrees to is the one that will work the best. Whatever system you use, you can expect some aspect of chores to keep reappearing on the family meeting agenda. This ongoing negotiation, although time-consuming, is important to the success of the democratic process. The idea is to encourage a feeling in children of cooperation and a willingness to do their share because they are part of the family. The use of an external reward system would undermine this goal. There is no need to pay children to do chores.

Once your children learn that you will take their problems seriously, listen respectfully, and use mediation fairly, they will start using the agenda sheet to write down problems they have with their siblings. If one child is bothered by something that a sibling has done, he or she will learn to write it on the agenda sheet, knowing that the problem will be dealt with equitably at the next meeting. This can prevent conflicts from erupting into major fights.

It is important to take all of your children's agenda items seriously, no matter how trivial they may seem. My daughter once wrote the word "burping" on the agenda. At the next meeting, she explained that her brother's loud burping bothered her. He replied that everyone had a right to burp, and that she did lots of things that bothered him, such as chewing gum loudly with her mouth open. (Meetings can become quite animated at times!) They finally reached the following agreement: He promised to stop burping loudly if she agreed to chew gum with her mouth closed. They never had a problem with this issue again.

After you have been holding family meetings for several months, you may notice some week that meeting day arrives and there is nothing on the agenda. When this happened in our family, we always held a meeting anyway, to give appreciations and make announcements, because my children never wanted to skip a meeting.

Reaching consensus

I recommend striving for consensus rather than voting, because it is worth finding solutions that everyone is happy with, even when this requires more time. Consensus means that each solution should have 100 percent agreement among all family members before the next agenda item is taken up. When consensus is hard to reach on a specific issue, the chairperson can ask if everyone agrees to end the discussion, but to have that issue be first on the agenda at the next meeting. Perhaps it is possible to reach consensus on a compromise solution. In our family, no one wanted the responsibility of cleaning the bathtub each week. It seemed as if there was no solution to this problem, so I suggested that we clean the bathtub only every other week, and take turns. Everyone agreed to this compromise solution, and my children willingly cleaned the bathtub every two months, when it was their turn.

Consensus is also hard to reach when an item on the agenda is a conflict of values rather than a conflict of needs. If you think that your son's hair is too long, or you don't like your daughter's choice of friends, it is important to realize that those are conflicts of values, and that your child's behavior does not interfere with any of your own needs. Whether or not your child does his homework or eats his broccoli are also conflicts of values. Another is if you are bothered by the mess in your child's own, private room. (An exception to this might be if you are trying to sell your home, and want it to look nice for prospective buyers.) When your children's behavior has no tangible effect on you, it will be very difficult to gain their cooperation in changing that behavior. I therefore recommend that you restrict the agendas of your family meetings to issues that have a tangible effect on you, such as issues of noise, use of the TV or the family car, help with chores, and messes in the common areas of your home.

When parents ask me how they can influence their children to adopt good values, I reply that the most effective way to share your values is to model them in your own life. By using a democratic approach to discipline and refraining from all authoritarian methods such as punishments or rewards, your children will be more likely to adopt your personal values, because they will respect you. However, it is important to realize that some of their values may be different from yours. For example, I enjoy having my room tidy and free of clutter. Although my daughter, like me, kept her bedroom fairly neat, my son did not. I finally decided that it was none of my business.

Follow-up

One advantage of family meetings is that they eliminate the need for nagging. If a solution is not followed during the week, the person who notices this can simply write the item on the agenda again. At the next meeting, the family can discuss the consequences of not following the agreed-upon rules until a consensus is reached on that.

I had a problem with my children leaving their shoes, jackets, backpacks, books, and toys in the living room, so I wrote 'stuff in living room' on the agenda. During the next meeting I gave a clear "I-message" statement describing my feelings, instead of a criticism of their behavior. I stated that this mess bothered me, I was embarrassed when friends came to visit, and I was afraid I might stumble. I asked for everyone's help in finding a solution. My children replied that they were very tired after school and didn't want to walk all the way to their rooms to put their belongings away. After much discussion, we finally came to an agreement that they could drop their belongings in the living room when they came home from school, but put them away by dinnertime each day.

This worked beautifully at first, but after about a week, my children started forgetting to put their things away before dinnertime. Instead of nagging them, I simply wrote it on the agenda again. At the next meeting, they asked me to remind them, but I replied that I didn't like to nag. Instead, I suggested that we could have some kind of nonverbal reminder. My children had previously agreed to take turns setting the table, so one of them proposed that whoever set the table would put something at the place of anyone who had left a mess in the living room. We finally came up with the idea of simply turning the person's plate upside down as a gentle reminder that that person could not eat until he or she cleaned up the mess. Everyone agreed to this.

One day, soon after this discussion, my daughter noticed that her brother had left his dirty socks in the living room, and gleefully turned his plate upside down. Another day, I was surprised to see my own plate upside down, and noticed that I had left some packages on the living-room floor. It is important to remember that consequences apply to adults as well as to children. We had no further problems with this issue, and continued to use this reminder until my children left for college.

Consequences should never be implemented without consensus. Otherwise, the system will slip back into an authoritarian approach, and the children will become resentful and rebellious. It is well worth the time and effort to reach mutually agreeable solutions, because children are usually quite willing to follow rules and accept the consequences that they themselves have helped formulate.

Advantages of family meetings

There are many advantages to having family meetings. Appreciations help to enhance self-esteem and contribute to family cohesiveness. Fights and arguments between siblings generally decrease, and you will find that you can abandon all forms of punishments, rewards, and nagging. Family meetings also foster a sense of responsibility and mutual cooperation. I was pleasantly surprised one day when my daughter spontaneously decided to organize one of our kitchen drawers, even though we had never discussed this chore at a family meeting.

The long-term effects of family meetings are also numerous. Parents who raise their children with a democratic approach to discipline and attention to children's feelings and needs usually find that their children do not need to rebel during adolescence. The parent/child relationship remains one of mutual respect, with each person willing to honor the other's needs. In our family, we actually had fewer conflicts during our children's adolescence than when they were younger. Finally, through the process itself, children learn valuable communication, mediation, and conflict-resolution skills, gaining firsthand experience with a true democratic system. These are skills they can use for a lifetime.

About Aletha Solter

Aletha Solter, PhD, is a developmental psychologist, international speaker, consultant, and founder of the Aware Parenting Institute. Her books have been translated into many languages, and she is recognized internationally as an expert on attachment, trauma, and non-punitive discipline.

Aware Parenting is a philosophy of child-rearing that has the potential to change the world. Based on cutting-edge research and insights in child development, Aware Parenting questions most traditional assumptions about raising children, and proposes a new approach that can profoundly shift a parent's relationship with his or her child. Parents who follow this approach raise children who are bright, compassionate, competent, nonviolent, and drug free.

For more information about family meetings, see Aletha Solter's books, Cooperative and Connected and Raising Drug-Free Kids.